Unpacking the Myth of Emotional Intelligence

The “Emotional Intelligence” book by Daniel Goleman presents a myth that emotions have intelligence and can learn to guide us because “Our passions, when well exercised, have wisdom; they guide our thinking.” So, with our emotional intelligence guide, “In a very real sense we have two minds, one that thinks and one that feels”, which gives us two different kinds of intelligence – rational and … irrational? Illogical? Unreasonable? Ludicrous? Thoughtless? Stupid? Mindless? Emotional? Ah, we will go with emotional. That leads us to “In a very real sense, we have two brains, two minds – and two different kinds of intelligence, rational and emotional.”

How does this even make sense?

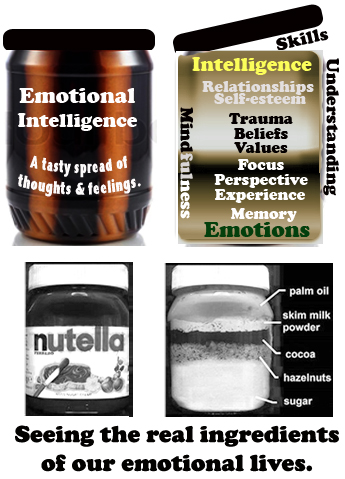

The questionable logic of emotional intelligence is difficult to understand when you look closely, because it seems apparent that emotions, thoughts and memories are different brain functions and abilities. Sort of like, Nutella isn’t an ingredient, it is the end result of mixing together many different ingredients. Emotional intelligence mixes together many different ingredients too.

The myth of emotional intelligence begins with redefining intelligence, which is the ability to reason, to learn, understand or deal with new or trying situations. Given this definition, we can see that emotions don’t fit, because emotions don’t learn.

Going further, there is no research or evidence of any emotion actually providing guidance or direction or ability to deal with a new or trying situation. Even using our most basic emotion of fear, we are still given five options – fight, flight, engage, freeze or fawn – which pretty much covers every possible action we could take. So, fear gives us power and we think what to do with that power. That insight reveals that emotions are very powerful but are not intelligent.

Next, think of “not intelligent” as being the same as “not rational”, and define intelligence, not as an ability to learn, but instead use the definition of rational, which is thinking based on facts or reason and not on emotions or feelings. Now, using rational as the definition for intelligence, we can see that emotions are indeed irrational. They are irrational because they have no intellectual abilities.

So, the emotional intelligence myth claims emotions are intelligent but irrational, and then defines being irrational as a new type of intelligence. Creating a new definition so that intelligently solving a problem in the real world can be rational or irrational/emotional. Now, irrationally dealing with a new situation is a sign of intelligence. Emotional intelligence.

Unfortunately, such irrational thinking habits that we can learn and be guided by our emotional abilities doesn’t really work. Emotional reasoning doesn’t actually solve issues or provide insights but just changes how we see reality and are usually referred to as cognitive distortions.

Cognitive distortions are habits of thinking that you use to consistently interpret reality in an unreal way. This is not a new idea.

If I may digress for a moment, the concept of cognitive distortions began in 1957, when American psychologist Albert Ellis created what he called the ABC Technique of rational beliefs. The ABC stands for the 1) Activating event, 2) Beliefs that are irrational, and 3) Consequences that come from the belief. Ellis wanted to prove that the activating event is not what caused the emotional behavior or the consequences, but rather what did was the beliefs and how the person irrationally perceives the events that aids the consequences. This idea was further expanded when psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and cognitive therapy scholar Aaron T. Beck started to notice these automatic distorted thought processes when practicing psychoanalysis with depressed clients. He realized that his patients had distorted thought processes which lead to 1) focusing on negative self-talk, 2) catastrophizing minor external setbacks, 3) mindreading other’s harmless comments as ill-intended, 4) using emotional reasoning that feelings are facts, and several other distortions.

Building upon their insights, psychologist Eugene Sagan coined the term “the pathological critic” to describe our critical inner voice that encourages us to use cognitive distortions to put ourselves down and reduces our self-esteem.

So, going back to the irrational thinking of “emotional intelligence,” we could conceivably use the term “emotional reasoning,” which is a cognitive distortion. Emotional reasoning is defined as “You assume that things are the way you feel about them.”

A prime example of emotional reasoning is how many politicians define their opponents or conflicts in terms of how they feel about them, using a whole lot of feelings and very little facts. Such as Democrats calling Republicans angry and harsh conservatives, and Republicans calling Democrats soft and stupid liberals. While such outbursts are emotionally intelligent, they are not accurate or useful.

Moving past the pathological critic’s negative inner voice that puts us down with negative cognitive distortions, we have a new inner voice – the “Vulnerability Guardian.” The vulnerability guardian is our all-powerful inner voice that unconditionally supports everything we do and uses positive cognitive distortions to avoid any uncomfortable responsibility or self-reflection regarding our thoughts and actions.

Politicians love this one too. They can remain invulnerable when they don’t have to acknowledge any reality they don’t like or doesn’t feel comfortable.

Now, listening to our vulnerability guardian, we can avoid any real change or growth when we are wrong by using the “Pivot Escape.”

The pivot escape occurs 1) when you realize that your information or view is incorrect, which is confirmed by feeling uncomfortable or vulnerable, and 2) then instead of acknowledging the correct info, and being open to growth or change, 3) you pivot or jump to another point or issue to allow yourself to maintain your narrative of being right, which is confirmed by you feeling good about your choices or perspective. This pivot or jump feels much better than actually having to admit or deal with any change, responsibility or error on your part. You are never vulnerable to change … or growth.

In defining intelligence as rational or emotional (irrational) thinking, it significantly impacts how we see our emotions. This confusing definition creates new issues that inhibit and confound the development of effective skills to recognize and regulate our own emotions, as well as deal with the emotions of others.

The first issue is that defining irrational emotions as intelligence and also rational thoughts as intelligence creates the illusion that thoughts and emotions are essentially the same thing, or can be taught to be the same thing. That our emotions and thoughts can be used to gain wisdom, insights and guidance. That we can learn from our emotions. As previously discussed, this is not true on many levels starting with the basic brain functioning of emotions originating from the amygdala and thoughts from the cortex; that their neurological development and paths are distinctly different; and over time their impact on brain development and behavior is vastly different. In contrast, it is more direct to recognize emotions as irrational power and thoughts as rational guidance or directions.

The second issue of the emotional intelligence myth is that intermingling thoughts and emotions makes it difficult to effectively recognize and deal with thoughts or feelings.

For example, if someone gets a math problem wrong and is told that it is wrong and to redo it, that is helpful to learn and get the correct answer, even if it might feel uncomfortable being told their results are wrong. Feeling bad or anxious when making a mistake while learning something new is not addressed. In this situation, thoughts but not feelings are addressed.

In contrast, if someone feels too angry, a red-light emotion, they are often told to not feel so angry and calm down, which is invalidating their feelings and stopping the development of skills to recognize and manage their anger. This focus to calm down and not be angry ignores where their anger is coming from. Did they get angry because someone wouldn’t give in to their unreasonable demands? For example, an unwanted sexual advance. In focusing on addressing how to change only the emotion of anger, the underlying irrational belief or cognitive distortion, which are thoughts, go unaddressed. Then, they may assume that since anger is an inappropriate response in reaction to someone refusing their sexual advances, they may try feeling sad or jealous as a better emotional approach to overcoming someone’s resistance to an unwanted sexual advance. In this situation, emotions, but not thoughts are addressed.

Now, if an emotional power perspective is used, recognizing emotions as irrational power and thoughts as rational direction, the response might address thoughts and feelings. That it is ok to be angry and then shift the focus to discuss where their anger came from, which would lead to discussing respect and consent regarding a person’s right to say yes or no to unwanted sexual advances. This approach might also help reduce future anger issues from developing and may encourage skill development to manage their anger, as well as sexual urges.

A third issue of the myth is that if thoughts and emotions are considered essentially the same thing, that is being a type of intelligence, then we can evaluate and judge emotions, just like thoughts, as good, bad, immoral or destructive. “Destructive emotions are those emotions that are harmful to oneself or others.” Going further, we can blame our emotions for our actions based on our emotional intelligence abilities. Then, with a focus on our emotions, we are less aware of how important our values, beliefs, trauma, memories and focus are on impacting our thoughts, feelings and actions.

Furthermore, given the issues of confusing thoughts and emotions and judging emotions as good or bad and blaming them for our choices, a fourth issue quickly becomes apparent which is a negative effect on interpersonal communication skills and relationships. When emotions are stuffed down and salient thoughts are unaddressed, the process of having meaningful dialogue often becomes difficult. Coming from an emotional intelligence perspective, stuffing down emotions might be considered useful to give yourself time to gain insights and learn from your emotional wisdom to guide your thinking. From an emotional powers point of view, stuffing down emotions usually leads to bigger emotional explosions down the road.

In summing things up regarding the emotional intelligence myth, a paired association seems to most accurately and insightfully reflect and represent the essential issues in a very concise fashion: Emotional Intelligence is to Military Intelligence as Emotional Power is to Military Power.

Pingback: BCA Holistic Mental Health Therapy: Quality Process - Emotional Powers